It was so terribly cold. Snow was falling, and it was almost dark. Evening came on, the last evening of the year. In the cold and gloom a poor little girl, bareheaded and barefoot, was walking through the streets.

--------------

These are the first few sentences of Hans Christian Andersen's 'The Little Match Girl', which you can read in full here. I first read it in Belgium on the recommendation of my friend Heathcote and I have just translated the first few paragraphs of it for my written expression class homework. The post's going to weave in and out of a few themes, so stay alert, and if your attention wains, the important bit's under the stars~

As you know, and as the logo of this blog regularly reminds, I have been campaigning with the Communist Party of Japan. Everyday in the newspapers we are presented with politics as political, that is, the ins and outs of party politics, what Cameron said about Brown, which policies are directed to which voter block, which way the polls are pointing. Far more interesting to me is the relationship between politics and culture, and indeed it is very likely that my dissertation next year will explore Japanese modernist literature through the lens of Zizekian cultural criticism to explore the underlying messages and politics or the Japanese liberal intelligentsia on the brink of Japan's decline into Fascism. And I get pleanty of high brow academic politics with the JCP, whether it's discussing constitutional systems, the differing international meanings of Trotskyism or whether Japan truly experienced 'democracy' before the war. But as a person who is prone to thinking too much, to over-rationalising things, to neglect the practical in favour of the theoretical, I am grateful to the JCP for awakening in me that relationship which is so often overlooked, but yet is the most essential, which is that between politics and people.

Every Saturday, from 10PM to around 11:30 the JCP, together with the wider 反費困 - Anti Poverty Campaign go to the south side of Kyoto station and give food and clothes to the homeless. I've been going the last couple of weeks and intent to go whenever possible. It is a practical, humanitarian ethos that the JCP have revealed time and again in the short time I've campaigned with them. Beyond feeding the homeless, they conduct 'labour consolations' with young people around Japan, where they interview people on the streets, give advice about finding employment, accessing welfare or joining unions. This also entails getting people to fill in questionnaires about their employment situation (or lack thereof...) which are relayed to the welfare office so that welfare and employment policy can better meet the people on the street's needs. JCP city meetings are just as likely to what a certain homeless person likes to eat, or safe places for someone to get changed, as they are to talk about policy and election campaigns. The only other political party who dealt with issues in such a grassroots way that I can think of (though as a strictly non-violent party the JCP would surely dismiss the comparison) is the Black Panther Party and their Free Breakfast for Children program which attempted prove the worth of socialist ideology with a working example of a socialised distribution scheme aimed at alleviating hunger in the poor.

Yesterday was the first time I got to meet some of the homeless people the party devote so much attention to. One old man sleeping inside the station was doing better that some others. He had a wife and son in the city, but for reasons he doesn't speak he can't return to them. Owing to his life long work at a nearby market, he had something of a pension and basic health-care coverage. For this, he is still homeless. Another old man has traveled the world, speaks very decent English and still dreams of starting his own business in Hong Kong. For this, he is still homeless. And this seems like as good a place as any to jump into the Japanese welfare system. -

What is readily apparent to foreigners, and widely known about Japan is that it is a hierarchical society with much emphasis placed on one's vertical relationship to one's superiors and inferiors. What is less widely known among the lay-person is that there is also a horizontal axis known as 'in-group, out-group'. This social structure is (traditionally, and it must be stressed that Japan is a country of 130 million people with huge internal cultural and personal variation) so ingrained that it is evident in the grammar of the language, where the Worker A of Company A speaks to Boss A with respectful language that show's the boss' superior position, but when he meets worker B of Company B, Worker A will talk about Boss A with humbling language, because in the face of an outsider, Company A operates and one unit, one in-group regardless of the hierarchy within it. To do otherwise is not simply a faux-pas but is actually grammatically incorrect.

These relations are repeated in the economic structure. The first barrier against poverty is company welfare. This is the security system that ensures that those who work stable, full time, unionised jobs will, in return for working all out for long hours, be looked after, financially, legally, whatever. This privatised welfare system served Japan very well during the boom years, but now more and more people are working unsteady, part time, un-unionsed jobs, where they can be fired at a day's notice and have nothing in the way of a pension or health coverage.

Where company welfare fails, what is known as family welfare is often expected to pick up the slack. Here is where people borrow money from, or move in with parents, aunts and uncles, brothers and sisters.

If you have a good job, and you have a good family, you are in the in-group. But as the presence of these English speaking, well educated homeless people shows, in this economic climate, people who were once 'in' have found themselves 'out' and this is where public welfare must step in. Increasingly the government is willing to play a role in protecting those who need it most. Though health-care isn't free (it is a universal system with the patients paying 1/3 of the costs), there is assistance for the poorest. Across the nation is the Living Assistance scheme, which provides the very poorest with a variety of monies for everything from money to buy nappies, to money to pay the rent. Kyoto, being a progressive city, holds days where free health care and check ups are given along with other services. Kyoto's pitiful 18 shelter beds are in fact comparatively high, and the city has negotiated a deal with a hotel with high vacancies to put the homeless up for free in these harsh winter months. All of this takes money, which is paid for by taxes. I have not met any 'welfare scrounges', rather simply people who's very sustenance depends on the public pocket and who are either physically unable to work, or simply unable to find work because they are old. Similarly, behind the tabloids' frequent stories about those who abuse the system, the vast majority of recipients of welfare in Britain are people who would work if they could or if there were any jobs to be found. Food for thought when complaining about taxes.

One can see the system for it's failures and successes. For the welfare offered, there are those who are unable to receive it. Some people literally are unable to walk all the way to the welfare office. Some people find it impossible to wade through the characteristically Japanese bureaucracy involved. Still more are unwilling to take the Living Assistance because of personal pride - an emotional response perhaps difficult to understand for Westerners but beautifully conveyed in the Studio Ghibli classic - Grave of Fireflies. It was touching to see the cycle of one man volunteering with us who had himself been a recipient of the Living Assistance, had got himself an apartment and now works with the Anti Poverty Campaign convincing others that there's no shame in accepting help. But for those who have slipped through all other layers of protection, the JCP and Anti Poverty Campaign are there providing hot rice balls and soup, blankets and socks.

*******************************************************************

Kyoto has very quickly become very cold. The Japanese boast that Japan, unique among nations, has four distinct seasons. Obviously the existence of the four words 'winter, spring, summer, autumn' bare no relation to this theory of Japanese-exceptionalism at all. But sure enough, right on schedule, a mere few days before the first of December the temperature drops to see-your-breath-in-the-air-and-3-jumpers-cold. There is an old woman called Noriko-san who sleeps in front of Kyoto Station. She's tiny and walks very slowly, when she walks, is very quiet but has a sense of humor and know what she likes and what she doesn't. She doesn't like being around people and is reluctant to take up the offer to stay in this hotel for free, though there is progress and week by week we push, we can only hope. She is talked about often and fondly among the volunteers and in official meetings. We gave her soup and rice balls, and her t-shirt and jumper not being anywhere near enough, wrapped her in 3 blankets. She looked sweet as could be, more blanket than body, and as one volunteer said, a lot like a snowman. Warm fuzzy feelings abound, this is what it feels like to save the world.

And then Iida-san, leader of the Kyoto Youth and Student section of the JCP, my go to guy in the party, in the midst of a lot of "isn't it cold" talk drops it. "Isn't it? She could die."

I cycled back home, nose running, scarf wrapped up to the mouth, looking forward to my heated room. She doesn't have a heated room. None of them do. She could die.

So this is my Christmas Appeal -

To my friends in Kyoto I like to get any old items of clothing, or perhaps more realistically a bit of money to buy as many Uniqlo HeatTeq clothes, and blankets as possible to ensure that this winter none of Kyoto's homeless have to die of the cold.

To my friends and family in Britain, I ask you to think of the homeless, and the millions in horrendously substandard housing around the country and donate whatever you can to Shelter, who are a ridiculously brilliant charity who's services are especially needed over these next few months.

If my story's not convinced you, go back to the top and read Andersen's, it's only short, honest.

Big love, sleep safe, tight, and warm.

xxxxxx

Sunday, 29 November 2009

Monday, 23 November 2009

Topic unknown, author unknown

Though autumn arrives

for all men, I alone plumb

the depths of misery.

The sadness resides, it seems,

not in autumn but in me.

----------------------

That is poem 185 of the Kokin Wakashu (The Anthology of New and Old Poems), a 10th century classic of Japanese poetry (which you can read in Engish translation h-h-h-h-here)! The first few sections of the collection are organized by season, with a vague 'narrative' of familiar seasonal events, such as the arrival of certain birds, or the blooming of certain flowers, to give it a sense of direction.

Pervading the collection is a sense of 物の哀れ - mono no aware, which roughly translates as the 'pathos of things' but refers to the tragic beauty in the fact that all things fade. In the Japanese cultural psyche, this feeling is strongly linked with spring cherry blossoms and autumn leaves, which are ssen as all the more beautiful for their brevity. It's a phrase that is loaded with both Orientalist and Nihonjinron connotations, in the case of the former exemplifying how different the Japanese are to other nations, and to how effeminate, pre-modern they are, in the case of the latter proving how different the Japanese are to other nations, and to how much more sensitive, aesthetically refined they are. Few practicing Japanologists would use the phrase without heavy doses of irony or self-awareness (My literature teacher responded to a friend using the term regarding a Japanese film by drawing his fingers into a gun and shooting himself) but it's definitely apparent in everything from the canonical texts of modern Japanese literature to comedy coming-of-age anime/ It's an aspect of Japanese culture I find very attractive, as a person who can feel nostalgia for events as they're unfolding, or even experience nostalgia in anticipation of events that haven't yet happened. But anyway, this is pre-ample, the starting poem is especially, gloriously miserable, and here are some photos of Kyoto being pretty.

I accidentally cycled into a temple and found this sunset.

View from the first train after a night out in Osaka.

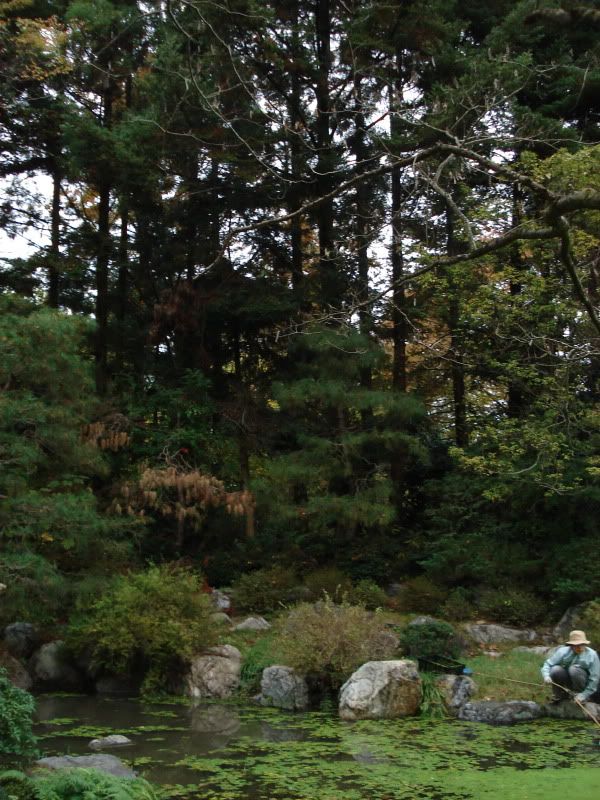

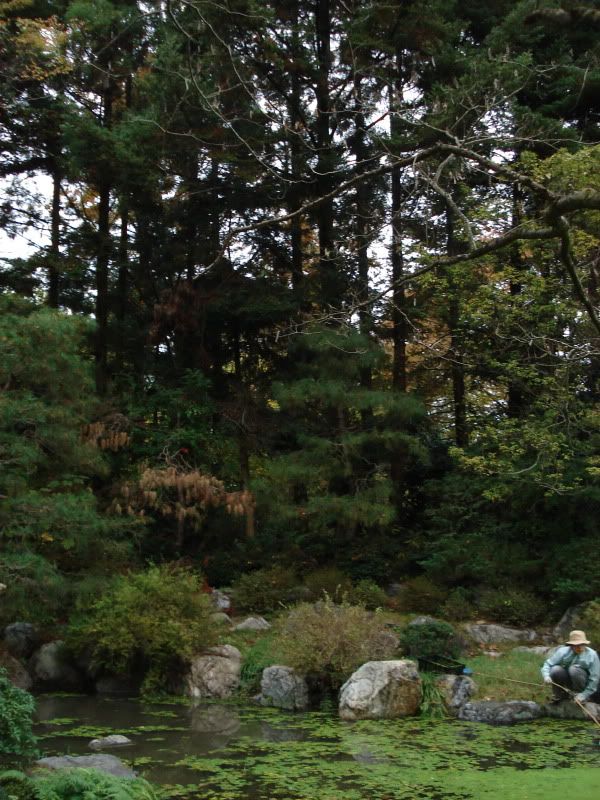

紅葉 - Momiji, Autumn leaves, on an amazing day out to the Kyoto Botanical Garden.

What am I like?

Enjoy! But also cry a bit, and then you too can be mono no aware.

xxx

for all men, I alone plumb

the depths of misery.

The sadness resides, it seems,

not in autumn but in me.

----------------------

That is poem 185 of the Kokin Wakashu (The Anthology of New and Old Poems), a 10th century classic of Japanese poetry (which you can read in Engish translation h-h-h-h-here)! The first few sections of the collection are organized by season, with a vague 'narrative' of familiar seasonal events, such as the arrival of certain birds, or the blooming of certain flowers, to give it a sense of direction.

Pervading the collection is a sense of 物の哀れ - mono no aware, which roughly translates as the 'pathos of things' but refers to the tragic beauty in the fact that all things fade. In the Japanese cultural psyche, this feeling is strongly linked with spring cherry blossoms and autumn leaves, which are ssen as all the more beautiful for their brevity. It's a phrase that is loaded with both Orientalist and Nihonjinron connotations, in the case of the former exemplifying how different the Japanese are to other nations, and to how effeminate, pre-modern they are, in the case of the latter proving how different the Japanese are to other nations, and to how much more sensitive, aesthetically refined they are. Few practicing Japanologists would use the phrase without heavy doses of irony or self-awareness (My literature teacher responded to a friend using the term regarding a Japanese film by drawing his fingers into a gun and shooting himself) but it's definitely apparent in everything from the canonical texts of modern Japanese literature to comedy coming-of-age anime/ It's an aspect of Japanese culture I find very attractive, as a person who can feel nostalgia for events as they're unfolding, or even experience nostalgia in anticipation of events that haven't yet happened. But anyway, this is pre-ample, the starting poem is especially, gloriously miserable, and here are some photos of Kyoto being pretty.

I accidentally cycled into a temple and found this sunset.

View from the first train after a night out in Osaka.

紅葉 - Momiji, Autumn leaves, on an amazing day out to the Kyoto Botanical Garden.

What am I like?

Enjoy! But also cry a bit, and then you too can be mono no aware.

xxx

Labels:

Kyoto,

Literature,

Photo slurge

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)